Committed to telling the story of Louisiana during the war and the part taken by her sons

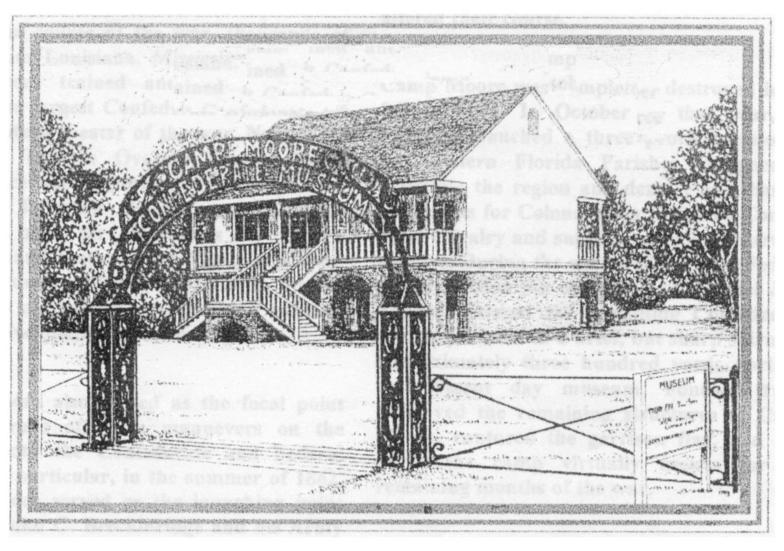

Our Museum is open from Wednesday thru Saturday from 10:00 AM until 3:00 PM. We are closed for all National Holidays.and close from Thanksgiving through the end of the year.

The grounds at Camp Moore are open 7 days a week from daylight to dusk for pedestrians. You are welcome to walk the grounds and take our self-guided walking tour. Please respect the grounds and leave them in the same condition you found them.

Registration Form

Join us on Facebook

Short History of Camp Moore

On April 8th, 1861 Governor Thomas Overton Moore of Louisiana made the initial call for 3000 troops to join the Confederacy. Southern forces attacked Ft. Sumter in Charleston, SC harbor on April 12th, 1861. President Lincoln made an immediate call for 75,000 Northern volunteers to crush the rebellion. President Jefferson Davis made another call for another 5,000 sons of Louisiana. Men all over Louisiana began to rush to form companies of men to join the army. This was usually done by a local civic leader or previous officer in the local militia having bar-b-ques, meetings and socials to have the opportunity to stir the patriotic fervor of the local men. Advertisements would be taken out in local papers and flyers distributed. As the companies formed in a local area, they were generally sent off with new uniforms and national flags by the ladies and citizens of the area. The local companies would elect their own officers and petition the State of Louisiana to offer its services. They would then be ordered to New Orleans to receive accoutrements and weapons seized at the Baton Rouge Arsenal in January.

These first companies to form were sent to New Orleans at the site of the Metairie Race Course (present-day Metairie Cemetery) to train and organize. This camp was named Camp Walker. However, this site was a poor choice. There was no drinking water supply close by. The land was low and unhealthy. Yellow fever epidemics plagued the area at times of the year. Too many visitors from New Orleans visited the camp, making order and discipline difficult to maintain. By May, 1861, Brigadier General Elisha Tracy, the commander of Camp Walker, issued orders to Lt. Col. Henry Forno and Capt. James Wingfield, land owners in upper St. Helena Parish, to go into the piney woods of St. Helena and find a new campsite. On May 12th, 1861, orders were issued for all troops presently at Camp Walker to begin moving to the new camp at Tangipahoa Station in St. Helena Parish. The site chosen was situated on the New Orleans, Jackson, & Great Northern Railroad, thus allowing easy access from New Orleans and points north. The land was high ground and bounded on two sides by water, to the south by Beaver Creek and to the east by the Tangipahoa River.

The men arrived and immediately began clearing a parade ground on which to do the elements of company and battalion drill. Campsites were set up according to the military rules of the day on the southern end of the camp. The new campsite was named Camp Moore, in honor of Louisiana governor, Thomas Overton Moore. General Tracy presided over the camp. Rules had just been established by Governor Moore in a Special Order stating how the companies were to be formed. There was to be a minimum of 64 privates, 8 non-commissioned officers and 3 officers. Companies that could not meet this minimum standard were disbanded and sent home. A large two-story commissary house and quartermaster store were erected on the western edge of the camp near the railroad. Just south of the commissary house, sutlers, merchants peddling their wares to the soldiers, began setting up shops along the sloped banks of Beaver creek. Among these sutlers were a couple of shanty restaurants, a photographer’s salon and several “booths of stores and refreshments”. Somewhere along this same line was a guard house, for those guilty of various infractions. In an ironic premonition of things to come, the first man to die at Camp Moore would die in an accident three days after the camp was opened. Private Bill Douglas of the soon-to-be famed Tiger Rifles of Major Robert Wheat’s command, was killed while doing guard duty at the railroad. An accident occurred while he was on the tracks and a train carrying cannon from Osyka, MS passed through camp.

Life for the volunteers at Camp Moore was anything but glamorous. The day started before dawn and the drill to make soldiers out of farmers and merchants was conducted until the early afternoon. A battalion parade was held each day so that the commander could see the progress of the men. Drill was only part of the reason for being there. The various companies also had to organize into ten companies which comprised a regiment. This was an unusual process as the various company commanders would politic to be put with other companies they considered themselves compatible with. When enough companies could get together, they would hold elections to elect a Colonel, Lt. Colonel and Major from the men. The regiment was then assigned the next number in line (the Fourth Regiment being the first to leave Camp Moore). The entire regiment was then sworn into service of the Confederate States of America and then usually shipped out within a few days. Meanwhile, other companies were organizing, new companies arriving and the process repeated.

At times, the space of the camp was overloaded and a new section in the upper part of the camp was coined “Camp Tracy”. It was located just east and southeast of the cemetery. The soldiers formed “messes” of 4-6 men to cook their rations. Many of the tents took on signs, signs of youthful exuberance and confidence. Some of these were labeled “Innocence Hall”, “Our Woodland Home”, the “Lion’s Den”, “Happy Retreat” and “Blood and Thunder”. While many men complained in letters of the rowdiness of some men, the mundane chores such as cooking for themselves and washing their own clothes, most letters expressed a contentment with the conditions. The loudest complaint was over a lack of proper rations, which seems to have occurred from time to time.

Between the middle of May, 1861 and the end of August, 1861, eight full regiments had been mustered into service and left Camp Moore, around 8,000 men. Most of these regiments were sent to Virginia. They would be the last as the war was soon to come to Louisiana.

Companies continued to stream into Camp Moore in the fall of 1861. It was during this time that one of two serious epidemics hit the camp. Measles outbreaks hit while the 16th, 17th, 18th and 19th regiments were being formed. Measles was particular hard on the companies formed from the rural parishes. Many of these men had never been exposed to the disease as children and deathly consequences resulted. Even the various complications were deadly and men died by the scores. There was no treatment, only but to make the patient comfortable and await recovery or death. These regiments soon left Camp Moore but the camp was hit again in the spring of 1862 and another deadly epidemic took scores of lives. By April, 1862, the Conscript Act had been instituted and those men coming to Camp Moore now, for the most part, were drafted or had accepted a bounty to enlist and had avoided being drafted. In late April, activity picked up at Camp Moore, though the new company numbers were waning. The Federal fleet under David Farragut passed the forts below New Orleans and the next day anchored at New Orleans, demanding the surrender of the city. Gen. Mansfield Lovell, commander of all army forces in New Orleans, had no artillery to challenge the ships. He had a meager force of several thousand militia. He saw the absurdity of challenging the Federal fleet and ordered all military personnel and stores to be sent to Camp Moore. Thousands of pounds of stores of every kind were brought to the camp. It is not known how long most of this material or even the men stayed there. Baton Rouge fell to the same Federal fleet in the second week of May, 1862.

Most of the organized regiments and battalions leaving Camp Moore in May, 1862 were sent to the Vicksburg area. By July, 1862, an organized effort was being formulated to oust the Federal forces in Baton Rouge. Gen. John C. Breckinridge arrived at Camp Moore on July 28th, 1862 with a mixed force of Alabamians, Tennesseans, Mississippians, Kentuckians, Louisianans and Arkansans. They stayed only two days before starting the long, hot march to Baton Rouge on July 30th. On the early morning of August 5th, 1862, the Confederates enjoyed an early tactical surprise and overwhelmed the Federal troops in Baton Rouge, but unsupported by expected naval help from the ironclad, CSS Arkansas, they were forced to abandon their gains due to Federal gunboats shelling them in the river. Breckinridge soon retreated to the Port Hudson area and began construction of fortifications there. This would be the last major organized effort to leave Camp Moore. The rest of 1862 saw the camp under the direction of Gen. Felix Dumonteil. Gen. Tracy died at an unknown place and time in 1862. Gen. Dumonteil spent much of his time rounding up deserters and conscripts, placing them into organized units.

Much of the activity around Camp Moore in late 1862 and early 1863 dealt with the movement of troops in and out of Mississippi and the movement of troops into Port Hudson on the Mississippi River. The Federals attempted movements from New Orleans to the area of Camp Moore but were continually stopped short of Camp Moore. There was only weak movement from the Baton Rouge area. Port Hudson and Vicksburg both fell to Federal forces in July, 1863, thus freeing up large numbers of Federal troops in the area. However, by this time, Camp Moore was typically only manned by a few conscripts and was a stopover for various Confederate cavalry commands moving through the area. It was not until the fall of 1864 that forces would move effectively against Camp Moore. On the evening of October 5th, 1864, about 1,000 troops from five different cavalry regiments and under the command of Col. John Fonda left Baton Rouge and moved out the Greenwell Springs Road. They passed Greenwell Springs, Williams Bridge near present day Grangeville and then on to Osyka, MS on the morning of the 7th. That evening a force of about 100 troopers entered Camp Moore and scattered the 50 odd conscripts located there. They then proceeded to destroy a vast quantity of stores including large quantities of gray cloth, a tannery, 2,000 sides of leather and scattered about 200 cattle. They also captured the garrison flag and sent it North.

The very next month, in the pre-dawn hours of November 30th, 1864, a large Federal force of 5,000 cavalrymen entered Camp Moore and spent the remainder of the day burning all buildings and looting the village of Tangipahoa. When they left toward the east, Camp Moore ceased to exist. The war was over for Camp Moore.

In time, nature reclaimed Camp Moore and for the next 30+ years, trees and briars grew where the men had drilled, camped and eaten their meals. The cemetery with its possible 800 graves became overgrown and forgotten. The people of the South would spend years trying to recover from the destitution caused by losing the war and the days of harsh Reconstruction that followed. Beginning in 1888, efforts by former veterans began, as appeals were made to the State of Louisiana for a sum of money to renovate and reclaim the cemetery at Camp Moore. By August, 1891, a new Confederate Veterans Camp was established at Camp Moore, being comprised of many local veterans that had passed through Camp Moore on the way to war. The first commander was Lt. Colonel Obadiah P. Amacker of Wingfield’s 3rd Louisiana Cavalry and a native of the area. Things really began to happen by then. Locals began to become active and eventually, by 1901, the 2 acres comprising the cemetery was donated by a lumber company to a local group.

Ladies groups in the form of the local United Daughters of the Confederacy took the charge. Finally, in 1902, money was allocated from the State of Louisiana to preserve the cemetery. By now, only one wooden headboard still existed, it being made of heart of pine. It marked the grave of 15 year-young Joe G. Harris of Bossier Parish. Joe was the provider for his family of at least one sister, his parents having died earlier. He came to Camp Moore with the Vance Guards (Co. A, 19th La. Inf.), caught measles and died in the fall of 1861. The wooden board disappeared over the years and even his gravesite is now unknown. Between 1903 and 1905, a fence was constructed around the cemetery. It was dedicated on June 3rd, 1905. The monument was then added and dedicated on October 24th, 1907. Over the next 50 years, a Board of Commissioners oversaw the upkeep of the cemetery. It was not until about 1960 that efforts were begun, mainly by ladies with the United Daughters of the Confederacy Chapter #562 at Camp Moore, to acquire additional land and build a museum at Camp Moore. Finally, in 1961, the Louisiana Legislature appropriated money for a museum and Governor Jimmie Davis signed the legislation. The new museum building was dedicated on May 30th, 1965. Miss Norma Lambert became the first curator and Mrs. Irene Morris succeeded her. In 1972, the operation of Camp Moore was placed under the Office of Historical And Cultural Preservation. Camp Moore flourished during the Centennial years and in the 1970’s, steadily building the collection of artifacts. In 1986, under pressure from Gov. Edwin Edwards due to budget shortfalls, Camp Moore was closed to the public along with many other historic sites in the State.

This would not be the end of Camp Moore, however. Interested individuals, along with the Camp Moore Camp, Sons of Confederate Veterans and the Camp Moore Chapter, United Daughters of the Confederacy organized the Camp Moore Historical Association and petitioned the State of Louisiana to allow them to reopen Camp Moore to the public. This was approved in 1992 with a 97 year lease to the Camp Moore Historical Association. Over those years, and on to the present, Camp Moore is operated by an all volunteer staff of interested individuals whose sole interest is to see the TRUE story of Camp Moore preserved for generations to come. The future of Camp Moore is up to the number of volunteers that are willing to step forward, much as they did in 1861. Without that effort, will the story of the tragic death of Bill Douglas on that summer day in 1861 be remembered? Will the agonizing death of 15 year-old Joe Harris be in vain and forgotten? Will nature once again reclaim this hallowed ground where as many as 800 sons of Louisiana left their hopes and dreams for all eternity? As you walk her grounds, it is easy to let the mind wander and you can almost hear the sounds of men marching, orders being barked and the rumble of horses moving across the fields. One can imagine the sounds around the campfire, the laughter, the telling of stories, the sound of the fiddle, banjo or harmonica. It is easy to visualize dozens of smoke streams so lazily lifting skyward from dew-covered ground on an early morning as the smell of coffee and bacon over open fires arouse still another sense. You might be able to picture a tent with friends comforting a sick and dying friend. Stopping under one of the large oaks, you might picture a young man writing a letter home to his wife or mother. Try to imagine a steam engine puffing to a halt and hundreds of young men disgorging from crowded flat cars and coaches to the cheers of thousands of their fellow Louisianans, cheering the new arrivals that would join them on their quest.

Camp Moore is historically correct, nothing more, nothing less. Help us insure the truth tomorrow by preserving our past today.